Osgood-Schlatter Disease: Top 5 ways to manage this disease

Osgood-Schlatter Disease is a common reason for young teenage clients to come into our clinics. If you have pain at the front of the knee, then this article is for you. Find out the specific causes of pain in the front of the knee, Osgood-Schlatter Disaese and our top 5 ways to manage this disease.

So what is Osgood-Schlatter disease?

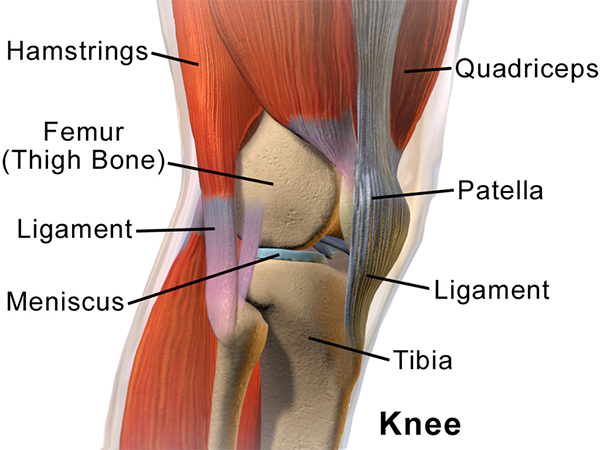

Osgood-Schlatter Disease (OSD) is the name for tibial tuberosity apophysitis. Specifically, inflamed bone at the site of the tibial tuberosity growth plate. The tibial tuberosity is the bony prominence at the top of the shin bone. This is where your patella tendon attaches. It can be a painful and very limiting condition.

The name came about after Doctors Robert Osgood and Carl Schlatter in 1903 recognised a pattern of symptoms in young athletic males. They concluded that OSD was a growth-related problem.

How do you know if you have Osgood-Schlatter’s?

OSD generally presents as pain at the front of the knee. This pain is at the site of the tibial tuberosity in active, growing adolescents.

Symptoms of OSD can include:

- Pain, swelling and tenderness to touch in the area of the tibial tuberosity

- Discomfort during exercise involving running or jumping

- Pain with kneeling or other direct contact

- Going up/down stairs, squats, or lunging can be painful

- Weakness in the muscles of the thigh (due to pain)

- The apophysis (or bony prominence) can become enlarged in later stages of the condition.

So what causes Osgood-Schlatter Disease?

Young teenagers who participate in running and jumping sports most commonly present with Osgood-Schlatter’s disease. It most commonly affects boys aged 11-15 years and girls aged 8-13 years.

As a child is growing, their developing bones go through differing stages. In the tibia or shin bone this can be related to when they are most susceptible to developing OSD.

- Cartilaginous stage: the tibial tuberosity is initially made of cartilage. This moves to the;

- Apophyseal stage: a secondary ossification centre (apophysis) develops at the tibial tuberosity. Next;

- Epiphyseal stage: the proximal tibial epiphysis unites with the tibial apophysis. Finally;

- Bony stage: when the growth plates fuse.

Growing young teenagers are at most risk of developing OSD when they (or their bones) are in the apophyseal stage. During running and jumping sports, there are repetitive strong quadriceps muscle contractions which pull on the tibial tuberosity. This causes a traction force.

This force is thought to disrupt the immature bone, resulting in the pain and swelling associated with OSD. Sometimes new bone growth can occur as part of the bodies healing process. This results in an enlarged bony lump in some cases.

A further cause of OSD can be a short quadriceps muscle (muscle at the front of the thigh) in comparison to the femur (thigh) bone. In an active growth spurt the lengthening femur grows faster than the quadriceps muscle can lengthen. This results in increased force where the tendon of the muscle attaches at the tibial tuberosity.

There are other biomechanical abnormalities that can be picked up by a physiotherapist which can indirectly affect the likelihood of developing/ or successfully treating OSD – these will be discussed under OSD treatment.

Diagnosing Osgood-Schlatter:

OSD is usually a clinical diagnosis. The treating clinician can diagnose the condition based on what the client tells them, and what the clinician can ascertain in clinic. Generally there is no need for further investigation (ie scans), unless the clinician is suspicious of other conditions. These could include bony fracture, malignancy or infection.

Management of Osgood-Schlatter:

OSD is usually managed well conservatively, under the guidance of a physiotherapist. Usually without the need for other interventions such as injections or surgery. There are many treatment strands in the successful management of OSD. Our top 5 most common ones that can be used together are outlined below:

Activity management:

Rest is an important tool in the management of OSD. Initially restricting higher impact or aggravating activities will reduce symptoms and allow the rehab programme to progress. In previous decades/generations teenagers diagnosed with OSD were told to cease all sport/activity for 6-12 months, or until symptoms had completely cleared for a sustained period of time – particularly devastating for a sport-mad young teenager!

It is common practice now to decrease load on the affected knee: which doesn’t involve ceasing activity completely, just managing the appropriate load so not to make the symptoms worse. Each case is different, and the treating physiotherapist will best manage the activity load depending on the presentation.

Ice/Anti-inflammatory use:

Ice is good to use on the sore point after activity or prescribed physiotherapy exercises. A sore tibial tuberosity can also be rubbed with an anti-inflammatory gel. We find a gel-wrap the most effective way to apply topical gel. Liberally apply the gel over the sore tibial tuberosity before bed, and wrap in glad-wrap overnight to ensure the gel is absorbed and not evaporated!

Knee brace:

Often a Cho-Pat original knee strap can offload the patella tendon, and dramatically decrease symptoms in those suffering from OSD. We stock these straps in various sizes in clinic.

Exercises:

Stretches are important in the early phase of rehab as the quadriceps muscle is generally tight as explained above.

Stretches for the gluteals, ITB, hamstrings and calf muscles are also commonly prescribed. Physical exam will often find these muscles to be tight.

Sometimes stretching the quadriceps can be too painful on the inflamed tibial tuberosity. Therefore massage and foam rolling can be beneficial for this muscle group.

Strengthening muscles of the core and hip, as well as around the knee is sometimes a key requirement to getting OSD under control. If the core and hip musculature are not controlling the pelvis and leg, it could be placing unnecessary extra load on the tibial tuberosity.

Foot control:

Foot biomechanics are important in controlling forces on the knee. A physiotherapist or podiatrist can prescribe certain exercises to aid in foot control. They can also prescribe the right type of shoe. Sometimes orthotics may need to be prescribed by a podiatrist to maintain adequate foot position to control the forces on the knee.

Overall:

Osgood-Schlatter is described as a self-limiting condition. Under the treatment guidance of a physiotherapist and podiatrist it can be managed well. Invasive treatment (such as injections/surgery) is generally not required. Full resolution of the condition happens once the tibial growth plates fuse. Unfortunately the condition may take some months to fully resolve.

If Osgood-Schlatter is affecting you or a member of your family, be sure to contact our clinic to be set-up with a thorough treatment programme under the guidance of a physiotherapist or podiatrist to ensure the best outcomes.

References:

Brukner P, Khan K. 2007. Clinical Sports Medicine (3rd Ed). McGraw-Hill, Sydney.

EHRENBORG G The Osgood-Schlatter lesion. A clinical study of 170 cases. Acta Chir Scand. 1962 Aug; 124():89-105.

Hiroyuki Watanabe, PhD, PT, Meguru Fujii, MS, PT, Masumi Yoshimoto, MS, PT, Hiroshi Abe, PhD, PT,Naruaki Toda, MS, PT, Reiji Higashiyama, MD, and Naonobu Takahira, MD. Pathogenic Factors Associated With Osgood-Schlatter Disease in Adolescent Male Soccer Players: A Prospective Cohort Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018 Aug; 6(8): 2325967118792192.

Shinya Yanagisawa, MD, PhD, Takashi Osawa, MD, PhD, Kenichi Saito, MD, Tsutomu Kobayashi, MD, PhD, Tsuyoshi Tajika, MD, PhD, Atsushi Yamamoto, MD, PhD, Haku Iizuka, MD, PhD, and Kenji Takagishi, MD, PhD. Assessment of Osgood-Schlatter Disease and the Skeletal Maturation of the Distal Attachment of the Patellar Tendon in Preadolescent Males. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014 Jul; 2(7): 2325967114542084.